1 Summary

It is possible to produce the appearance of a terrorist attack on the

United States by means that do not employ terrorists, as such, but by the

simple substitution of one aircraft for another, particularly when the

transponders of the aircraft involved are turned off. The only people who

need to be deceived by such an operation are the radar operators at air

traffic control (ATC) centers.

The scenario explored here, called Operation Pearl (after Pearl

Harbor), has been described in sufficient operational detail that sound

judgments can be made about a) feasibility and b) consistency with

evidence on the ground. At the time of this writing it is probably the

best available description of what probably took place on September 11,

2001.

Under the Operation Pearl scenario, the passengers of all four flights

died in an aerial explosion over Shanksville, PA and the remaining three

airliners are at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

2 Introduction

Since March of 2002, persons probing the web for further information

about the 9/11 attacks could not fail to encounter, sooner or later, a

scenario advanced by Carol Valentine. Called the "Flight

of the Bumble Planes" (Valentine 2002), it allegedly came from an

informant who would only identify himself as "Snake Plissken," the name of

the hero of the movie, Escape from New York (footnote

1).

The informant outlined the basic hijacking method in an email message

to Carol Valentine, comparing it to a flight of bumble bees. Watching bees

as they buzz around among flowers, it is very difficult to follow

individual bees, since they are always passing close to one another.

This metaphor translates into the flight of two aircraft in a confined

locale of airspace. If the separation between them is small enough, radar

operators will see not two aircraft, but one. On the morning of September

11, 2001, according to this scenario, all four "hijacked" aircraft landed

at a single airport or air base, transferring their passengers to a single

aircraft, the one that crashed in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, remotely

controlled aircraft of various types carried out the actual attacks. The

scenario, as presented by Valentine, consists of little more than I have

presented here.

Of course, there is a vast difference between an outline and a detailed

operational plan. It may turn out, for example, that any attempt to

imagine how a specific scheme is implemented runs into snags, as in the

attempt by Spencer

(2003) to get all four aircraft to one air base long enough for the

combined list of over 200 passengers to board a single aircraft, take off

and crash near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Spencer, however, assumed that

the takedown of aircraft coincided with the turning off of transponders.

In the present paper the scenario is modified to allow takedown prior to

the turning off of transponders, assuming that takedown occurred at the

first deviation of each aircraft from its flight plan. The refurbished

scenario has now been completed to a level of detail that makes it

possible to evaluate its feasibility, as well as its consistency with the

evidence, as presently acquired and developed.

A scenario named Ghost Riders in the Sky was previously constructed by

the author (Dewdney 2002). The purpose of that scenario was simply to

demonstrate that alternate scenarios that fitted all the facts (as then

understood by the author) could be constructed. The scenario involved

killing all the passengers and flight crew with a fast-acting nerve agent,

then triggering a software patch in the aircraft flight control systems to

direct the aircraft to their various destinations. However, when it became

evident that no Boeing 757 had actually struck the Pentagon (see The

Pentagon Evidence, also on this website), the scenario was rendered

invalid. The Ghost Riders scenario, like the Bush-Cheney scenario,

required that the aircraft that struck their respective targets were as

advertised, two 767s and two 757s.

The fact that the Ghost Riders scenario must now be rejected

illustrates the nature of this inquiry. As in science, hypotheses must be

formulated, then tested against the available evidence. If found wanting

in the light of that evidence, they must be rejected. It is normal in any

scientific inquiry to formulate and analyze more than one hypothesis

before one is found that actually works. The same remark also applies to

criminal investigations.

3 The Evidence Filter

Any scenario constructed to account for the events of September 11 2001

must pass a graduated test, as embodied in the following items. These fall

into three classes:

Suspicious circumstances

- Four of the named hijackers were not in the United States.

- The WTC towers collapsed without adequate heat stress.

- Smaller aircraft accompanied Flights 77 and 93.

- Most of the alleged hijackers were rather poor pilots.

- Evidence of the alleged hijackers developed too quickly.

- Westward excursion of Flights UA93 and AA77 are inexplicable as

terrorists hurrying to targets."

Anomalies

- The US Air Force failed to intercept any of the flights.

- The hijackers' names did not show up on passenger lists.

- The hijackers' faces did not appear on boarding gate videos.

- Black boxes were missing from all but one flight.

Contradictions

- The Pentagon was not struck by a large passenger aircraft.

- Cellphone calls alleged to have been made by passengers were

essentially impossible.

A successful scenario must at least explain the contradictions and

account for a majority of the anomalies. It is of course desirable that it

also account for the suspicious circumstances, but no scenario need stand

or fall in this regard.

It must be remarked that the only scenario ever supplied to the public

via the official media was the Bush-Cheney scenario, that Arab hijackers

seized control of the four aircraft and proceeded to pilot them into

national landmarks, killing both themselves and their passengers. Clearly,

the Bush-Cheney scenario, considered in detail, explains none of the

suspicious circumstances, none of the anomalies and is directly

contradicted by the facts adduced in the third category. As scenarios go,

it is a distinct failure.

4 Technical Elements

The two major technical aspects of the Operation Pearl scenario involve

radar and remote control. Radar technology has been with us since World

War Two, some 60 years ago. Remote control technology has been around in

various forms for at least twenty years. With a basic understanding of

both radar and remote control in relation to 9/11, it becomes possible for

the average citizen to think for himself or herself.

4.1 Radar Substitution

A radar screen is essentially a circular CRT (cathode ray tube — like a

television screen) that displays aircraft within the circular airspace

represented on the screen. Radar operators are the only people who can be

aware of what planes are in the sky and where they are going. The vast

majority of people are completely unaware of what is going on in any large

volume of airspace and, when an aircraft passes overhead, can usually not

tell one type from another, let alone what airline or aviation company may

own it. This observation, while something of a commonplace, has important

implications. If an organization wishes to substitute one aircraft for

another without anyone knowing it, the only people it has to deceive are

the radar operators.

The resolution of a radar screen is the size of the smallest point that

can appear there, approximately two millimeters in diameter — a "blip." A

typical radar screen, less than a meter in diameter, could therefore be

described as less than 500 "blips" wide. If the airspace represented on

the screen were 500 kilometers in diameter (approximately 300 miles, a not

atypical size), each blip would represent a piece of airspace that is more

than 500/500 = 1 kilometer wide.

In other words, as soon as two aircraft get within a kilometer of one

another, there would be a tendency for their respective blips to merge.

With half a kilometer separation or less, the two aircraft could easily

appear as one.

Of course, two aircraft that are that close together run a distinct

risk of collision — unless they are at different altitudes. Radar screens

are two-dimensional in that they represent airspace in the same way as a

map, with the vertical dimension of altitude suppressed. Thus, without

additional information in the form of a displayed altitude number, it is

impossible for a radar operator to tell whether two merged blips represent

a potential collision or not. Altitude information is displayed if an

aircraft's transponder is turned on, otherwise, the radar operator has no

idea of the altitude at which an aircraft happens to be flying.

If one aircraft happens to be within a half kilometer of another,

whether above that aircraft or below it, the radar operator will see only

one aircraft, as long as the two maintain a horizontal separation that is

no greater than half a kilometer (about 500 yards).

Imagine now two aircraft, both headed for the same approximate point on

the radar screen, both with their transponders turned off. One is well

above the other but, as the blips merge, both planes swerve, each taking

the other's former direction. The operator would simply see the aircraft

cross and would have no way to realize that a swap had taken place.

There are many other swapping patterns available. For example, one

plane could apparently catch up and "pass" another when, in fact, it

slowed after the blips merged, even as the other speeded up.

Another method involves the replacement aircraft climbing out of a

valley where it would be invisible to distant radars, even as the other

aircraft descended into the valley. Again, a radar operator would see a

more or less seamless flight without realizing that he or she had been

momentarily seeing not one, but two aircraft on the radar screen.

Of course, if the transponders are turned on, as explained in the next

section, such confusion is less likely to occur. Even in this case,

however, the deception can be complete if the aircraft switch transponder

codes.

4.2 Aircraft transponders

Every commercial passenger jet carries a transponder, a device that

emits a special radio message whenever it senses an incoming radar wave.

The signal carries the transponder code, a multi-digit number that serves

to identify the particular aircraft to radar operators at air traffic

control centers. The purpose of the code is to make it clear to ATC

operators which plane is which. Other information sent by the transponder

includes the altitude at which the aircraft is flying. Transponders were

implemented many years ago precisely for the reason that radar blips are

otherwise easily confused. Transponders make the radar operator's job much

easier.

The pilot of an airliner can turn the transponder on or off in the

cockpit. He or she can also change the code by keying in a new number.

Transponder codes for all aircraft departing from a given air traffic

control region are assigned by the ATC authority more or less arbitrarily.

The only important criterion for the numbers so assigned is that they all

be different. It sometimes happens that an aircraft entering the control

area carries the same transponder code as another aircraft that is already

in the area. In such a case, one of the pilots is requested to change his

or her code to avoid confusion.

4.3 Remote Control

A remote control system of the type used in this scenario uses a signal

interface that does two things: It reads signals from a ground station and

sends signals back to it. Both sets of signals must pass through the

aircraft's antenna system. In the Boeing 757 and 767 the antenna system is

located in the forward belly of the aircraft.

The outgoing signal from the aircraft would include a video signal from

a camera located in the nose or other forward portion of the aircraft.

Flight data such as control positions, airspeed and other instrument

readings are also included in the outgoing signal. The incoming signal

from the ground station would include the position of a virtual control

yoke (governing direction of aircraft), thrust, trim, and other essential

flight parameters.

The virtual pilot would sit in front of a reduced instrument panel and

a video monitor. A simplified control yoke or "joystick" control would

also be part of the operator's equipment. The remote pilot would watch the

instruments, as well as the video image, making continuing adjustments in

the aircraft's flight path, just as if he or she sat in the cockpit of the

actual aircraft.

Many claims of the attacking aircraft being under "remote control" have

appeared on the web since 9/11, but typically with little or no supporting

documentation. The claim of a pre-installed anti-hijacking system (Vialls

2001) has proved impossible to verify. Similarly, claims that Global Hawk

technology (USAF 98) was used are rampant, but do not quite fit the

specific version of Operation Pearl presented here. For one thing, the

Global Hawk system does not use remote visual guidance, but onboard

navigation electronics that bypass the need for direct, minute-by-minute

human control.

The system invoked for the attacks in Operation Pearl is based on the

Predator unmanned surveillance vehicle (USAF undated), a modularized

aircraft that can be broken into components for ease of shipping and rapid

deployment. One of the components includes a remote guidance module which

could be refitted to another aircraft (with appropriate modifications)

without the need to strip a predator vehicle. The predator operates under

remote human guidance from a ground station that, once deployed, would

require as few as two human operators during a "secure" operation.

A second possibility involves a system known as a "flight termination

system," manufactured by the System Planning Corporation. (SPC 2000) This

system permits hands-on control of a nearly endless variety of aircraft,

the control interface being to a large degree customizable. For the

purposes of the Operation Pearl scenario, either of these systems might

well be adaptable to the remote operations of nonmilitary jet aircraft.

Without question, however, the basic technology for the remote guidance

of aircraft has been on hand for many years. For a large intelligence

organization it would be a straightforward technical operation to install

a remote control system in virtually any type of aircraft, whether a large

commercial airliner or anything smaller. The aircraft carrying the

installation would be available and prepared in advance, then substituted

for the passenger aircraft it was meant to replace.

4.4 Electronic towing

An interesting but different form of remote control is invoked by the

Operation Pearl scenario in the "cleanup" phase, namely the disposal of

the three aircraft that did not crash in Pennsylvania or anywhere else. I

call this facility "electronic towing," It consists of two "black boxes"

that pick up signals from an aircraft's data bus, a shared electronic

pathway travelled by all electronic signals that control the aircraft.

(Spitzer 2000) Each black box can read the bus through the data bus

monitor, as well as insert information into the bus. Because the

connections are already available, installation of the boxes could be

completed in a matter of hours on any aircraft. In this relatively simple

form of remote control, one aircraft would be called the "slave," the

other the "master." In addition, two 2-way radios allow the black boxes to

communicate, specifically for the master box to send its signals to the

slave box. Under identical conditions, the slave aircraft will do

precisely what the master aircraft does. Such control signals could also

be taped and replayed later to invoke in the slave aircraft exactly the

same behavior as the master.

To initiate towing, the master aircraft takes off first, while the

slave aircraft remains on the runway, completely unoccupied. As soon (or

as late) as the pilot of the master aircraft wishes to, a recording of the

master signals is played over the radio to the slave aircraft, which then

takes off precisely as the master aircraft did. The slave will then follow

the master wherever the pilot of the master wishes to go. With a short

time delay in the control loop, the slave aircraft would appear literally

to be towed by the master, always maintaining the same distance and

position behind it. If the pilot of the master aircraft wished to

"unhitch" the slave, he could simply cut the control signal. Over the

ocean, the unhitched aircraft might fly until it runs out of fuel or it

might be blown up by implanted explosives.

5 Operation Pearl

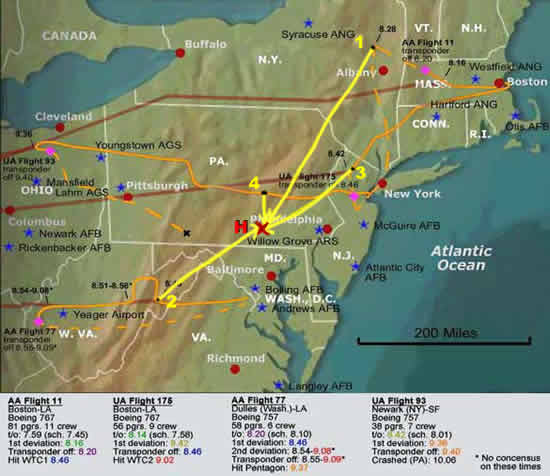

In the detailed scenario to follow, Harrisburg International Airport

was selected as the base of operations. However, any airport, airbase or

landing strip of suitable length within, say, 50 km of Harrisburg might

work just as well. The following table displays the takeoff times of the

respective aircraft from Boston's logan Airport, Newark International, and

Washington's Dulles Airport on the morning of September 11, 2001. Assuming

a takedown at the first deviation, the flying times to Harrisburg

International Airport are calculated and the arrival times of the

respective aircraft at Harrisburg are displayed. All flying times are

based on the assumption of an average airspeed of 805 km/h (500 mph). In

each case, 5 minutes is added at either end of the flight to allow for

takeoffs and landings.

| Flight Take-down |

Distance to Harrisburg |

Flying Time |

Arrival |

| AA11 8:16 am |

420 km |

32 + 5 min. |

8:53 am |

| UA175 8:42 am |

200 km |

15 + 5 min. |

9:02 am |

| UA93 8:42 am |

260 km |

20 + 5 min. |

9:07 am |

| AA77 8:46 am |

240 km |

18 + 5 min. |

9:09 am |

As a convenience, the takedown of Flight UA93 has been made

simultaneous with the aircraft's takeoff. Since the flight path was

directed toward Harrisburg, the takedown time is not relevant to the

calculation as it could have taken place anywhere along the route,

yielding the same result for arrival in Harrisburg.

As a feasibility check, we may now calculate whether there was adequate

time on the ground in Harrisburg to deplane three of the aircraft, loading

their passengers onto Flight UA93. Working backwards, the flight of UA93

from Harrisburg to Shanksville involved a distance of 144 km for a flight

time of 18 minutes. Thus, to "crash" at 10:06 am, it had to leave

Harrisburg no later than 9:45 am. This would give the agents of Operation

Pearl (see Appendix C) some 36 minutes to board

the passengers from the other flights onto Flight UA93.

A master timetable for the entire

operation has been provided at the end of this article. Readers may wish

to consult this table, along with the accompanying map,

in order to obtain a birdseye view of all four flights.

We will now examine key elements of the scenario in the form of

mini-dramatizations that place the reader in the scene, as it were. The

following sketches supply enough detail to provide a secondary check on

feasibility. I have used a compact notation to refer to the four

replacement flights, simply appending an "X" to the flight number. Thus

"UA175X" refers to the replacement aircraft for flight UA175.

5.1 The takedown

The morning of September 11 dawned bright and clear over Boston's Logan

Airport as crews arrived for the first flights of the day. The departure

lounge for American Airlines Flight 11 was already filling with passengers

when John Ogonowski, the pilot, and Thomas McGuinness, the second officer,

arrived to board their Boeing 767 and begin the preflight check.

As passengers slowly filed past the check-in counter and onto the

boarding ramp, the flight officers proceeded through the cockpit

checklist. The weather would be perfect for flying. Only one little detail

soured Ogonowski's day. He had been informed that an FBI antiterrorism

agent would be aboard the aircraft. Among the incoming passengers, a

nondescript gentleman in a business suit settled into a seat in first

class. Just as the giant turbofan engines began their warmup, a stewardess

reminded the gentleman, now scribbling on a piece of paper, to fasten his

lap belt.

"Certainly. Er, would you mind giving this note to the captain?"

She took the note forward, handing it to Ogonowski, who read it with

more than passing interest.

"Hmmm. I guess it's real. Take a look at this, Tom."

McGuinness read the note.

My name is Bill Proctor, FBI anti-hijacking

team. We have information that hijackers may be aboard the aircraft

today. I repeat, may. My partner and I are on this flight to prevent

such a happening. We wish our presence on board to be kept confidential.

I am in seat 7A. Thank you for your cooperation.

"I'd better take a look at this guy," said Ogonowski. Take her out

while I go back for some coffee."

The engines roared to life and the aircraft began to taxi out to the

runway. Ogonowski spotted the gentleman and pulled the note from his

breast pocket. The gentleman nodded and smiled back.

"I'm sorry. I still have to ask to see your ID."

"Certainly." The man handed Ogonowski a small wallet, flipped open to

reveal the famous logo.

On his way to the galley, Ogonowski scrutinized the passengers from the

corner of his eyes. Instinctively, he looked for swarthy, middle eastern

types, somewhat reassured to see none.

The takeoff was smooth and the 767 climbed into clear blue skies, with

several wisps of cirrus off to the west. About 15 minutes into the flight,

just as the flight officers were relaxing and thinking a hijacking rather

unlikely, another note arrived via the stewardess.

We have spotted two terrorists on board. I

must come forward to discuss the situation with you. Bill

"What the hell! Is this guy serious?"

"Jeez. I guess so."

Inside the cockpit, the gentleman wore a serious frown.

"We'll have to land at Harrisburg, where we have facilities to deal

with this problem. Use the 80.7 kHz frequency and do not engage in any

other radio activity at this time, please. Identify yourself as American

Flight 380 and tell them you have a faulty fuel pump in Number Two

engine."

"Where are the terrorists?"

"Don't worry, they're here. By the way, you must also turn off your

transponder. Now."

Ogonowski turned on the PA system.

"Ladies and gentlemen, we have experienced a slight difficulty with one

of our fuel pumps and must land to have it checked. American is sorry for

the delay. We'll have alternate transportation ready for you as soon as

possible."

The gentleman smiled, nodding approvingly. A murmur of groans and

complaints filtered into the cabin.

"One more thing. As soon as we touch down, proceed immediately to the

military hangars at the north end of the airport. We have a team of agents

there who will board the aircraft as soon as you can get the doors open."

Although Ogonowski sent no messages to New York ATC, he could hear the

chatter and knew something was up. About seven minutes before they would

land at Harrisburg, he heard that one of the World Trade Center towers was

on fire, having been hit by a "commuter aircraft," as the rumor had it.

Ahead of him the layout of Harrisburg Airport, faintly discernible in the

distance, grew slowly in size. The aircraft banked and made its final

approach. Unknown to Ogonowski, another Boeing 767 shadowed flight AA11,

below and slightly behind them. It climbed, even as flight AA11 descended.

More radio chatter revealed that aircraft had been ordered down all over

the United States. Ogonowski would be the first of many emergency landings

at Harrisburg International that day.

The 767 glided smoothly to touchdown, its air brakes howling. The

aircraft slowly rolled to a crawl, then turned onto a taxiway that led to

an Air National Guard hangar, where a man with orange batons waved them

in. As soon as the flight crew got the doors open, one of the group of

waiting officials rolled a large gangway to the open door and three agents

dashed up the stairs. One of them had a bullhorn.

"Ladies and gentlemen. We must ask that you leave the aircraft

immediately. Leave all personal belongings and carryon bags aboard the

aircraft. This includes cellphones. Do not attempt any cellphone calls, as

they could trigger any explosives on board. We'll begin evacuation from

the front of the aircraft."

Dutifully, the passengers streamed from the aircraft in orderly

fashion, making their way down the steep gangplank and joining a crowd

that had formed around another official.

"Ladies and gentlemen. It is now safe to tell you that you have just

escaped being hijacked by Arab terrorists. We will apprehend the suspects

and search the aircraft for bombs and other dangers to public safety.

Unfortunately, this procedure may take some time and we have no facilities

for you here. We'll have to put you on another flight, as soon as it

arrives. I realize that this is very inconvenient and we apologize.

However, you can think of yourselves as among the luckiest people in

America today."

As he spoke, two officials led a disheveled man in handcuffs down the

gangplank. He had olive-colored skin and a dark beard. A murmur went up

from the crowd.

"Where the hell did he come from?" muttered McGuinness. He had a

feeling of unreality in the pit of his stomach. He felt nauseous.

By then, another aircraft, flight UA175, had landed and was now taxiing

toward the same hangar. The officials herded the passengers into the

hanger, where they were told to wait. Then they went to greet the second

aircraft, where they repeated the procedure.

Tower personnel were of course aware of the two flights parked at the

Air National Guard hangar. They were aware that the aircraft were being

inspected by some kind of security team but, beyond that, they paid little

heed to the operation. They were too busy coordinating some very busy

airspace.

5.2 Swapping aircraft

At the New York air traffic control center rows of radar operators

"pushing tin," as they call it, monitored flights into and out of New York

airspace, talking to the pilots occasionally on their throat mikes. Each

operator had several flights to monitor, a job that guaranteed one of the

highest stress levels of any occupation in the travel industry.

The time was 8:37 in the morning. Operators were about to become aware

that something was amiss in their airspace. We pick up the conversation

between one of them (bold face) and the aircraft under his

responsibility. (NYT 2001) My commentary within the transcript has been

placed in square brackets.

"USA583 checking in at FL350."

"USA583 Roger."

"42-39 see the 823 FL350 reference that guy on left."

"I gave the FDX turns. Do what you want, reference the FDX."

" R49 310."

"FDX226 contact New York Center on 133.47. Good day."

"33.4 FDX3226 heavy."

"New York UAL 457."

"Sector 10 point out west of LRP 712 at FL410."

"Point out approved."

"UAL175 at FL310."

[The time was 8:40 am. United Airlines Flight 175 came on the air with

some information to report.]

"UAL 175 New York center. Roger."

"New York do a favor. Were you asked to look for an aircraft, an

American flight about about 8 or 9 o'clock 10 miles south bound last

altitude 290? No one is sure where he is."

"Yeah, we talked about him on the last frequency. We spotted him

when he was at our 3 o'clock position. He did appear to us to be at 29,000

feet. We're not picking him up on TCAS. I'll look again and see if we can

spot him at 24."

"No, it looks like they shut off their transponder. That's why the

question about it."

"New York UAL175 heavy."

"UAL 175 go ahead."

"We figured we'd wait to go to your center. We heard a suspicious

transmission on our departure from BOS. Sounds like someone keyed the mike

and said, 'Everyone stay in your seats.'"

O.K. I'll pass that along.

"It cut out." (UAL 175)

"IGN 93 line."

"Go ahead."

"UAL 175 just came on my frequency and he said he heard a suspicious

transmission when they were leaving BOS: 'Everybody stay in your seats.'

That's what he heard as the suspicious transmission, just to let you

know."

[Then US Air Flight 583 called in.]

"Center, where do you place him in relation to 583 now?"

"He's off about 9 o'clock and about 20 miles. Looks like he's

heading southbound but there's no transponder, no nothing, and no one's

talking to him."

"Hello New York good morning DAL2315 passing 239 for 280."

"DAL2315 New York Center. Roger."

"New York center DAL2433 310."

"DAL2433 New York Center. Roger."

[Four minutes later the time was 8:46 and the mystery had not been

solved. Flight 11 was flying an angular route south, then east. Other

flights continued to converse with New York ATC.]

"Direct PTW DAL 1489 heavy."

"Roger."

"DAL2315 contact the New York Center on 134.6. Have a nice day."

"134.6 DAL2315."

"34.6 3-4-point 6."

"USA429 leveling off at 350."

I'm sorry, who was that?

"USA429 leveling at 350."

"USA429, New York Center roger."

[As we will shortly see, the radar operator lost track of Flight AA11,

as evidenced by his queries of pilots in the area, as well as his failure

to make any connection between the World Trade Center fire (about to be

reported) and Flight AA11. It appears that the flight had simply been lost

in the swarm of blips that crowded every screen at the New York ATC.]

"Anybody know what that smoke is in lower Manhattan?"

"I'm sorry, say again."

"A lot of smoke in lower manhattan."

"A lot of smoke in lower Manhattan?"

"Coming out of the top of the World Trade Center building, a major

fire."

"And which was the one that just saw the major fire?"

"This is DAL1489 we see lower Manhattan. Looks like the World Trade

Center on fire, but its hard to tell from here."

"DAL1489. Roger."

"Let us know if you hear any news down there."

"Roger."

"DAL 1043 cleared direct PTW."

"Direct PTW DAL 1043."

[At 8:51 am, the operator was still in touch with Flight 175, asking

the pilot to change his transponder code.]

"UAL175 recycle transponder squawk code 1470."

"UAL175. New York."

[But at 8:52 am, things went wrong with Flight UAL175, as well.]

"UAL175 do you read New York?"

"DAL1489 do you read New York?"

"DAL1489. Go ahead."

"O.K. Just wanted to make sure you were reading New York. United,

United 175. Do you read New York?"

"IGN on the 93 line. Kennedy."

"IGN on the 93 line East Texas."

"IGN."

"Do me a favor. See if UAL175 went back to your frequency."

"UAL 175?"

"Yes."

"He's not here. East Texas."

"10 — Do you see that UAL175 anywhere? And do me a favor. You see

that target there on 3321 code at 335 climbing? Don't know who he is, but

you got that USA 583. If you need to descent him down you can. Nobody. We

may have a hijack. We have some problems over here right now."

"Oh you do?" [another operator]

"Yes, that may be real traffic. Nobody knows. I can't get a hold of

UAL175 at all right now and I don't know where he went to."

[The transcript reveals a new aircraft with transponder code 3321. The

aircraft has already climbed to 33,500 feet. This may have been the

replacement aircraft.]

"UAL 175 New York."

"New York 583."

"USA583 go ahead."

"Yes. Getting reports over the radio of a commuter hitting the World

Trade Center. Is that nordo [no radio] 76 [Boeing 767] still in the air?"

It is interesting that the initial report of the first WTC attack

involved not a 757, but a smaller commuter aircraft. From that point on

however, things got increasingly hectic at the New York ATC center.

Operators glanced at the screen space centered on Manhattan and eastern

New Jersey, trying to guess which aircraft was Flight 175.

On all screens there were often several aircraft without transponder

codes. Some of these were local flights, mostly smaller aircraft. The

presence of such blips would probably have made the radar operator's job

much harder. Taking one's eye off a suspicious aircraft to check other

aircraft in the area might make it impossible to be certain which aircraft

it was when the operator glanced back. This, in any case, was apparently

what happened.

5.3 The World Trade Center

It would have been an eerie experience to ride the 757 that we have

called Flight 175-X. Walking the aisles, we would have seen the seats all

stripped from the aircraft, the walls lined with fuel drums, like so many

token passengers. Cables ran up the aisle to the cockpit, where a large

black box sat on the floor, just in front of the control console. The

pilots' seats were missing. Some of the cables fed into several openings

in the console, others passed through openings in the floor into the

aircraft's belly, where the antenna system communicated with a ground

station.

At the ground station, an operator watched a color television monitor.

On it, he could see the Manhattan skyline looming steadily larger. He

adjusted the joystick slightly to the right, aiming for the south tower,

then pushed the stick forward slightly. The aircraft slowly descended

until it was level with the upper third of the still distant building. An

ironic smile crossed the operator's face. This was not exactly the

intended use of the Predator technology.

About a minute from impact, a steady crosswind that the operator had

not taken into account had pushed the aircraft off course to the east,

even as the tower loomed faster than he thought it would. He was going to

miss! Damn. He pulled the joystick sharply to the left.

Just when the corner of the south tower was about to disappear from the

screen , it swung back into view again, the building now appearing sharply

tilted to the right. He saw several rows of windows. Close, then very

close. In the last frame, he caught a glimpse of some office people

staring from one of the windows in horror. Then the screen went blank. To

think of how close he came to missing!

5.4 Back at the base

Under the operation Pearl scenario, the takedown of all four flights

would be conducted in the same manner, flights UA93 and AA77, being no

exceptions. By the time Flight UA93 arrived over Harrisburg, the alarm had

been out for a good 20 minutes. Flights were coming down everywhere.

Airport tower personnel, as well as those at all air traffic control

centers, were simply overwhelmed. In this context, bringing flights UA93

and AA77 into Harrisburg were relatively simple and secure operations

involving little more than switching to a new transponder number, landing

and proceeding to the same processing area. The same cover story still

worked, since it was not known at the time whether aircraft might be

targeted, as well as buildings.

The swap of flight UA93-X for flight UA93 would have been far less

exposed to radar than the swaps in the NY phase of the operation. As

Flight UA93 descended into the radar shadow of the Susquehanna valley

close to Harrisburg International, an executive jet rose out of the

valley, below and immediately behind the aircraft. The swap would have

been seamless, with Flight UA93 turning off its transponder about the same

time that the pilot of Flight UA93-X turned his on. Flight UA93-X then

turned north to follow an erratic path to the west as far as Cleveland

before looping back to head for southern Pennsylvania.

The search for bombs on Flights AA11 and UA 175 may have already been

completed by the time that Flight 93 touched down at 9:07 am. The

officials in charge of the operation nevertheless had a good 20 minutes to

search flight UA93 before hurriedly boarding all the passengers into the

one aircraft, an operation that could have been carried out in 20 minutes.

As the passengers boarded Flight UA93, the officials held a special

conference with pilot Jason Dahl and First Officer LeRoy Homer.

"Fellows, we've made a thorough check for bombs on board, and we're

sure it's clean. Unfortunately, we have some problems with the other

aircraft, so we're going to have to keep them grounded for the time being.

We don't have proper facilities for all these people here, so we're going

to have to ask you to take them all to Dulles where they can be looked

after properly. We'll send all personal goods and luggage along on one of

the the other aircraft, as soon as we have completed our work. We'll have

to board the other passengers now, without delay. You will be picked up by

a military escort aircraft as you leave. Please be sure to follow that

aircraft and stay in communication with it. Frequency will be 118.7 MHz.

all the way. Fly at the same level of 4000 feet. If it should happen to

deviate from its flight path, it may be checking something out. Just stay

on course for Dulles. Your escort will rejoin you soon enough."

Pilot and first officer nodded, then climbed the stairs, entered the

cockpit and began the preflight check for the second time that morning.

Meanwhile, passengers filed into the aircraft, urged on by the officials,

until the aircraft was full. As it happened, flight 93 had just enough

seats to accommodate the passengers of all four flights.

At 9:45 the 757 roared off the runway at Harrisburg and set course for

Washington, even as a military-looking all-white aircraft rose from low

altitude to fly off their port wing.

"This is your Escort Bravo One. We're not very fast, here." said the

military pilot. "Reduce your airspeed to 400 knots and stay directly

behind with minimal separation."

"I've seen that kind of aircraft before," said Homer.

"Yup. That's an A-10 Warthog," said Dahl. "And she's armed to the

teeth. See the missiles under the wing?"

"Warthog? Funny name."

"Actually, it's called the Thunderbolt, but I guess everyone thinks the

thing is too ugly to be called anything but a warthog."

5.5 The Crash at Shanksville

The two aircraft climbed out along the valley of the Susquehanna, then

headed southwest along a succession of valleys, emerging at last into a

large, relatively flat basin, partly forested and dotted with farms and

villages. Ahead of them, the white aircraft, flight UA93-X, suddenly

turned off and began circling around to the east, descending as it went.

Shanksville resident Susan Mcelwain watched the white aircraft pass

directly over her minivan:

"It came right over me, I reckon just 40 or 50 feet above my van," she

recalled. "It was so low I ducked instinctively. It was traveling real

fast, but hardly made any sound. (UF93 2001)

"Then it disappeared behind some trees. A few seconds later I heard

this great explosion and saw this fireball rise up over the trees, so I

figured the jet had crashed. The ground really shook. So I dialed 911 and

told them what happened . . . "

"There's no way I imagined this plane — it was so low it was virtually

on top of me. It was white with no markings but it was definitely

military, it just had that look. It had two rear engines, a big fin on the

back like a spoiler on the back of a car and with two upright fins at the

side. I haven't found one like it on the internet. It definitely wasn't

one of those executive jets. The FBI came and talked to me and said there

was no plane around."

The description of the mystery aircraft given by Ms Mcelwain happens to

match only one military aircraft currently in use by the US armed forces,

namely a (repainted) A-10 Thunderbolt, a heavily armed aircraft used in

ground support roles. (McChord 2003) Several other witnesses saw the same

aircraft, both before the crash and after it, circling the area. (Flight

93, 2001)

Two area residents, both quite close to the crash scene, heard missiles

being fired. One, a Viet Nam veteran, was quite sure about what he had

heard.

Mcelwain and many others heard one or two tremendous explosions rock

the sky over Shanksville. Debris rained down for miles around. One engine

landed nearly a mile from the alleged crash site. Body parts, luggage,

scraps of metal, bits of in-flight magazine plummeted or fluttered to the

ground a mile or more away.

The white aircraft turned, took one more pass, then headed back to its

base of operations. Mcelwain called 911.

The Shanksville "crash" of Flight 93 presents us with a number of

mysterious reports of a midair explosion (or explosions) as well as the

presence of a white "mystery jet" seen in the area by many local

residents.

The midair explosion was heard by virtually everyone in the area, of

course. The debris field resulting from the explosion was apparently much

more extensive than what would result from an ordinary crash, with all the

debris within a narrow compass laterally to the incoming flight path. New

Baltimore resident Melanie Hankinson, who lives some eight miles from the

crash site, found paper debris from the aircraft, including remnants of

United Airlines in-flight magazine, Hemispheres. Other debris, including

body parts, were scattered over a space of miles. One of the engines were

found a "considerable distance from the crash site," according to State

Police Major Lyle Szupinka.

Shanksville Mayor, Earnest Stuhl, has stated that at least two area

residents, both living within a few hundred yards of the debris field,

heard missiles being fired. One of the witnesses, a Viet Nam veteran, had

heard missiles fired from aircraft many times during his tour of duty and

claimed that it could not be anything else.

5.6 The Attack on the Pentagon

About the time that Flight AA11-X struck the north tower of the World

Trade Center in New York, Flight AA77-X took over from Flight AA77. Like

Flight UA93, Flight AA77 dropped into one of the numerous valleys that run

the length of the Alleghenies, possibly the valley of the Shenandoah

River. Meanwhile, Flight AA77-X, an executive jet, fled westward across

West Virginia before looping back, close to the border of southern Ohio.

At this point, the pilot turned off his transponder and headed straight

for Washington, DC.

By 9:30 am Flight AA77-X was already over Virginia, closing rapidly on

the capital. As it approached the Pentagon from the west, another smaller

aircraft, possibly a cruise missile, came into the Pentagon from the

southwest. It came very fast. Flight AA77-X banked sharply to pass over

the Pentagon from the same direction, then flew off to its base. Although

visible on local radar as an overflight, it was confused with the incoming

missile, which would have been visible as a second blip. Operators would

have been led to assume that the second blip represented the overflight.

The small military aircraft (or missile) slammed into the lower half of

the 80-foot high wall of the Pentagon, its fuselage punching a hole in the

two-foot thick limestone block wall.

5.7 Disposal

Getting rid of the original aircraft was trickier than one might

suppose. One could not simply wash off the paint with an acid scrub and

sell the aircraft to a third world country. Nor could one break the

aircraft up and sell the parts. Indeed the parts, thousands of them, were

all stamped with serial numbers that were registered to their respective

aircraft. They could be traced. For this reason, it would have been much

cleaner to dump the aircraft in the Atlantic Ocean.

Perhaps it was not until nightfall of September 11 that the disposal

operation started. By then each aircraft had been fitted with slave

technology. The master aircraft had already flown out over the Atlantic,

the signal from the data bus monitor having been transmitted back to shore

and recorded. It would then have been a simple matter to replay the tape

to each of the three "non-existent" aircraft at half-hour intervals. Each

aircraft would have gone through exactly the same motions as the master

aircraft, continuing its flight out over the Atlantic Ocean — until the

implanted bomb destroyed it. Under the Operation Pearl scenario, the three

aircraft ended up in pretty much the same state as the Bush-Cheney

scenario alleges. The locations are quite different, however.

Inspiration for the electronic tow technology came from the eyewitness

account of two aircraft sighted by a New Jersey resident and his wife

(names witheld by request).

"Several days before 911, my wife and I were walking on Long Beach

Island. It was late in the afternoon when I looked out over the ocean and

saw these two passenger jets flying toward us, due west. They were flying

amazingly low and amazingly slow. I was amazed to see these two jets were

flying closely behind the other [sic], nose to tail, and what was most

amazing was that they were perfectly spaced, about fifty feet apart, with

absolutely no fluctuations in their spacing. It looked just like one plane

was towing the other. They flew right over our heads, and I watched them

as they flew westward."

Under the operation Pearl scenario, the strollers witnessed a final

test of the master/slave control system.

6 The Evidence Filter

We are now in a position to review the evidence and its relationship to

the Operation Pearl scenario described above. Below each item in the

original checklist, I have placed a brief explanation of the relationship.

Suspicious circumstances

- Four of the named hijackers were not in the United States. The

alleged hijackers were not on the aircraft, in any case. Their names may

have been selected from a list of lapsed or stolen passports.

- The WTC towers collapsed without adequate heat stress. The lack of

passenger corpses, luggage, etc, had to be concealed by burial.

- Smaller aircraft accompanied Flights AA77 and UA93. Surrogate

aircraft were used as substitutes for the originals.

- Most of the alleged hijackers were rather poor pilots. The alleged

hijackers were not aboard the aircraft, in any case.

- Evidence of alleged hijackers developed too quickly. Evidence was

planted in order to have the story develop quickly.

- Westward excursion of Flights UA93 and AA77 are inexplicable as

terrorists hurrying to targets. The excursions gave time to load all the

pasengers onto Flight 93.

Anomalies

- The US Air Force failed to intercept any of the flights. No

interceptors were deployed since their pilots would have reported the

substitute aircraft.

- The hijackers' names did not show up on passenger lists. The

hijackers were not aboard the aircraft.

- The hijackers' faces did not appear on boarding gate videos. The

hijackers were not aboard the aircraft.

- Black boxes were missing from all but one flight. Black boxes were

not present on attacking aircraft

Contradictions

- Aircraft striking the Pentagon was not a large passenger aircraft.

Flight AA77 did not strike the Pentagon.

- Cellphone calls made by passengers were highly unlikely to

impossible. Flight UA93 was not in the air when most of the alleged

calls were made.

Expanded timeline for Operation Pearl

Time

|

Event

|

| 7:59 am |

UA11 takes off from Boston's

Logan Airport |

| 8:14 am |

UA175 takes off from Boston's Logan

Airport |

| 8:16 am |

First deviation of AA11 north of Albany,

NY |

| 8:20 am |

AA77 takes off from Washington's Dulles

Airport |

| 8:20 am |

AA11 transponder turned off |

| 8:30 am |

First swap: Flight AA11-X takes over,

transponder off |

| 8:35 am |

Beginning of NY ATC transcript |

| 8:40 am |

UA175 transponder is turned off |

| 8:42 am |

UA93 takes off from Newark, NJ |

| |

First deviation of UA175 over northern NJ |

| 8:46 am |

Second swap: Flight AA77X

takes over, same t-code |

| 8:46 am |

AA11-X strikes north tower of WTC |

| |

Nationwide alert begins |

| 8:53 am |

Third swap: Flight UA175X takes over,

transponder off |

| |

AA11 lands at Harrisburg |

| 8:54 am |

End of NY ATC transcript |

| 8:55 am |

AA77X transponder is turned off |

| 9:02 am |

UA175X strikes south tower of WTC |

| |

UA175 lands at Harrisburg |

| |

Fourth swap: Flight UA93X replaces UA93 |

| 9:07 am |

UA93 lands at Harrisburg |

| 9:09 am |

AA77 lands at Harrisburg |

| 9:37 am |

AA77X overflies the Pentagon, aircraft or

explosion at Wedge 1 |

| 9:45 am |

UA93 takes off from Harrisburg |

| 10:06 am |

UA93 crashes near Shanksville, PA |

Footnote 1: The plot of the movie, set in a decaying future New

York ruled by warlords, involves the rescue of the President of the United

States who is being held for ransom. Snake Plissken (played by Kurt Russel)

is released from jail by authorities eager to use his talents to rescue

the President.

References

(USA Today 2001) USA Today. 2000. Weapons of destruction. Accessed from

http://www.usatoday.com/graphics/news/gra/gflightpath2/frame.htm on

July 5, 2003.

(Dewdney 2002) Ghost riders in the Sky. Feral News. Retrieved from

http://feralnews.com/issues/911/dewdney/ghost_riders_1-4_1.html May

15, 2003.

(Flight 93, 2001) How did Flight 93 crash? Retrieved from

http://www.flight93crash.com

May 20, 2003. Note: this site uses mostly local and national media

sources.

(McChord, 2003) A-10 Thunderbolt. McChord Air Museum. Retrieved from

http://www.mcchordairmuseum.org/REV%20B%20MAM%20COLLECTION%20a-10%20%20BORDER.htm

(NYT 2001) The New York Times. October 16, 2001, Transcript of United

Airlines Flight 175. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/16/national/16FLIGHT175-TEXT.html July

4, 2003.

(Ostrovsky & Hoy, 1990) Hoy C, Ostrovsky V. 1990. By Way of Deception.

Toronto, Canada: Stoddart.

(Serendipity 2002)

http://www.serendipity.li/wtc.html

(SPC 2000) FTS Flight termination system. 2000. System Planning

Corporation, Langley, VA. Retrieved from

http://www.sysplan.com/ May 17 2003. See

http://www.sysplan.com/Radar/FTS/ (flight termination system) and also

http://www.sysplan.com/Radar/CTS/ (command transmitter system)

(Spitzer 2000) Spitzer, C. R. 2000. Digital Avionics Systems:

principles and practices. The Blackburn Press (McGraw-Hill), Caldwell, NJ.

(UF93 2001) United Flight 93 Crash Theory Home Page. 2001. How did

Flight 93 Crash? Retrieved from

http://www.flight93crash.com June 10, 2003.

(USAF no date) RQ-1 Predator unmanned aerial vehicle. United States Air

Force Fact Sheet. Aeronautical Systems Center, USAF, Langley, VA. No date

on document. Retrieved from

http://www.af.mil/news/factsheets/RQ_1_Predator_Unmanned_Aerial.html

May 18 2003.

(USAF 98) Global Hawk: U. S. Airforce Fact Sheet. Global Hawk.

Aeronautical Systems Center. USAF Langley, VA. Retrieved July 4 2003 from

http://www.af.mil/news/factsheets/global.html

APPENDICES

A: The Basic Timeline

(All times are ante meridian or am, EDT)

| Flight |

Departure |

Deviation |

Transponder |

Hit |

| American 11 |

7:59 am |

8:16 am |

8:20 am |

8:46 am |

| United 175 |

8:14 am |

8:42 am |

8:40 am |

9:02 am |

| American 77 |

8:20 am |

8:46 am |

8:55 am |

9:37 am |

| United 93 |

8:42 am |

9:36 am |

9:40 am |

10:06 am |

B: Table of aircraft

| Flight no |

Equipment |

Airport |

On board |

| Flight 11 |

Boeing 767 |

Boston Logan |

81 passengers, 11 crew |

| Flight 175 |

Boeing 767 |

Boston Logan |

56 passengers, 9 crew |

| Flight 77 |

Boeing 757 |

Wash. Dulles |

58 passengers, 6 crew |

| Flight 93 |

Boeing 757 |

Newark Intn'l |

30 passengers, 7 crew |

C: Estimates of equipment and personnel used in

Operation Pearl

The following lists represent the core requirements in equipment and

personnel required to execute Operation Pearl. Additional equipment as

well as operatives playing minor roles are not included. Also not included

are the operatives running "Operation Footprint," the flight training

program for approximately ten Arabs from a variety of middle eastern

countries.

Equipment

- 1 Boeing 767 fitted with remote guidance systems

- 3 Executive-sized jet aircraft, one fitted with a remote guidance

system

- 1 A-10 Thunderbolt

Personnel

| 2 agents on each of four aircraft |

8 |

| 10 agents at the base of operations |

10 |

| 4 agents to set up WTC demolition explosives |

4 |

| 2 agents as flight crew on substitute or escort aircraft |

6 |

4 agents as technicians to install RC controls

(also to act as remote pilots) |

8 |

| |

36 |

This number is certainly an underestimate, but easily mustered by any

large intelligence organization. Under the Operation Pearl scenario, the

most likely perpetrator would be Mossad, Israel's spy agency. An

arm's-length relationship with the Bush administration, with neocon

elements acting as go-betweens, would enable Rumsfeld, Bush and other

members of the US administration to disclaim any "specific" knowledge of a

forthcoming attack. (See Ostrovsky and Hoy, 1990.) |